February 16th marks the 30th anniversary of Keith Haring's death. Here's how he changed the face of contemporary art and how his artistic legacy lives on.

‘All of the things that you make are a quest for immortality. Because you’re making these things that you know have a different kind of life,’ said Keith Haring in 1988, just after he had been diagnosed with an AIDS-related illness. By 1990, aged only 31, he would be dead. ‘[My works] don’t depend on breathing, so they’ll last longer than any of us will,’ he had continued. ‘Which is sort of an interesting idea, that it’s sort of extending your life to some degree.’

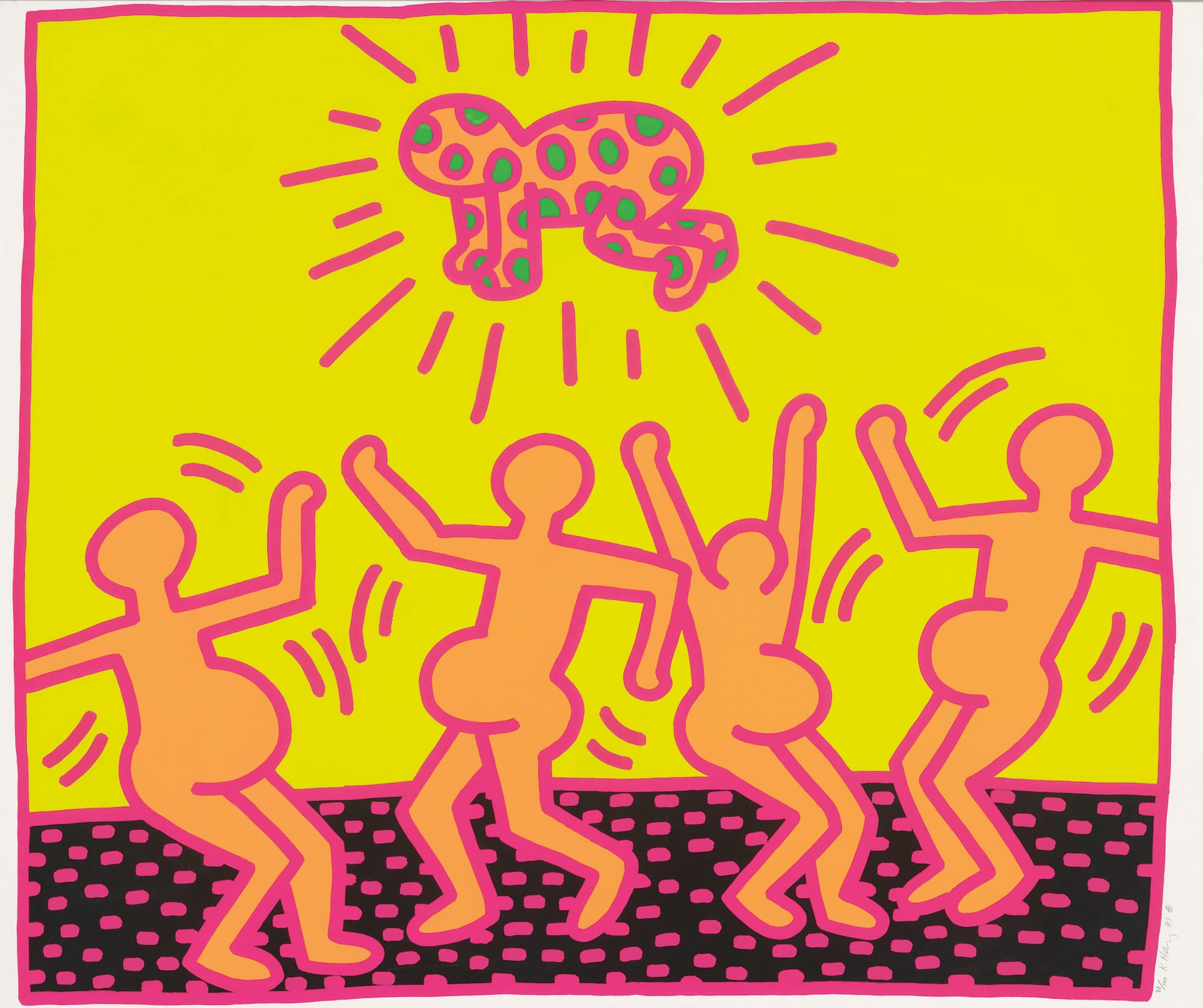

A cutesy style, with a political undertone – Haring had a message to tell

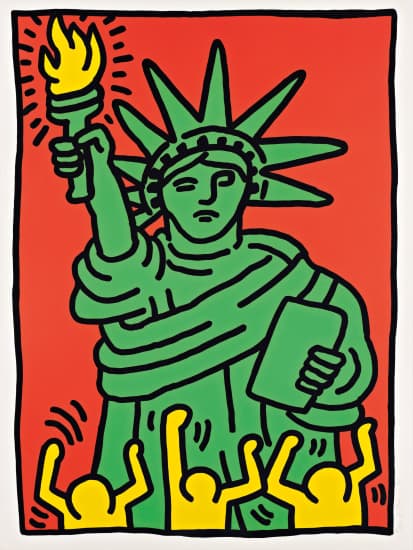

Haring was right, and his name is now synonymous with street art. His graffiti-esque creations, depicting a potpourri of babies, hearts, people and flying saucers, are recognised worldwide: cute, bright, simple and fun, they’re uplifting and joyful. Though his prospective mortality inevitably reared its daunting head, his art had never really been about himself, nor about forging a legacy; instead his works had been a commentary about society – as with his famous ‘Crack is Wack’ mural - and the need for change, addressing topics such as apartheid, nuclear war, Aids, capitalism and the climate.

He cared not for the critics, nor the accepted concept of ‘art’

Such important topics were nonetheless addressed in a gleeful pop-art style that grabbed young people’s attention and initially baffled the critics, who saw it as mainstream and lowbrow. Not that Haring cared: while studying at the School of Visual Arts on East 32nd Street in the late seventies, he had written, “The public has a right to art/The public is being ignored by most contemporary artists/Art is for everybody.” No wonder then that whilst still at SVA Haring started ‘tagging’ - adding his signature sketch of a crawling child, the ‘radiant baby’, alongside other’s graffiti. He quickly took his street art a step further, drawing upon the black paper that filled empty advertising spots by the subway– he’d scrawl on these in chalk. He had a natural talent for working with the space provided, and for working quickly, without preparation. This, on occasion, led to his arrest, but it also led to him building a public following. His posters, if not rapidly covered over, would often be stolen. And collectors started to track him down, eager to buy pieces. He needed a dealer to help him handle the fame; Tony Shafrazi became that man.

Without intending to, he became the street art darling of the celebrity scene

If Haring’s reputation had been already swelling, his first solo show (he had almost 50 in his lifetime,) in 1982 sealed it. He was suddenly part of the it-crowd, hanging out with Yoko Ono, buddying up with Madonna, hob-nobbing with David Bowie. Fame, alas, had its downside and by 1984 he was no longer able to do his spontaneous paintings on the subway – there was no point, they’d be stolen and resold immediately for top dollar.

He was forever a man of the people

It was a sad and unintended outcome for a man who wanted his work to be widely available to the public at affordable prices, so he opened up The Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in 1986. Some saw this as being a sell-out and brazenly commercial. Haring didn’t see it that way. If anything, it was his way of putting two fingers up to what he viewed as ‘the elitist establishment.’ As he said, ‘my work was starting to become more expensive and more popular within the art market. Those prices meant that only people who could afford big art prices could have access to the work.’ His work, he believed, was created for other artists and for ‘real people, people who don’t have any art background…but who respond with complete honesty from deep down inside their hearts or their souls.’

He turned the art world on its head

And by opening up the art world and turning it on its head, by taking art back from the snooty elite and sharing it with those he was speaking up for, Haring had his most lasting effect. For his has been a vivid, populist approach that has been - and still is - emulated by the likes of Banksy, Invader and Zevs. What would he make of the frenzy with which collectors and investors battle for his work in the great auction houses, paying in the millions for his iconic pieces? A mixture, perhaps, of annoyance and amusement.

He left his mark, physically and philanthropically

But he’d no doubt be delighted by the fact that there is public work of his in Antwerp, Berlin, San Francisco, Paris and Melbourne. That some of it features in hospitals, schools and an LGBT community centre. That his mural in Pisa, on the side of the Sant’Antonio Church, still exists, as too does the one at the Carmine public swimming pool in Greenwich Village. And that the Keith Haring foundation he established in 1989 continues to thrive, enriching the lives of underprivileged children and supporting hundreds of Aids-related organisations.

He knocked art off its pedestal

His desire and aim for his work, he once explained, was ‘a more holistic and basic idea of wanting to incorporate [art] into every part of life, less as an egotistical exercise and more natural somehow… taking it off the pedestal. I’m giving it back to the people, I guess.’ He succeeded.