In honour of International Women’s Day, we take a special look at Tracey Emin and Yayoi Kusama, whose eminent careers have helped to pave the way for female artists.

From the revolutionary quilts of Faith Ringgold to the skeletal structures of Louise Bourgeois, the history of female contemporary art is extremely rich. To try and create a synopsis of the many ground-breaking female artiststhat have contributed to this would be both reductive and frankly, impossible. Instead, and in honour of International Women’s Day, we celebrate two of the most highly regarded female artists working in contemporary art, Yayoi Kusama and Tracey Emin, and detail everything you need to know about these pioneering creatives.

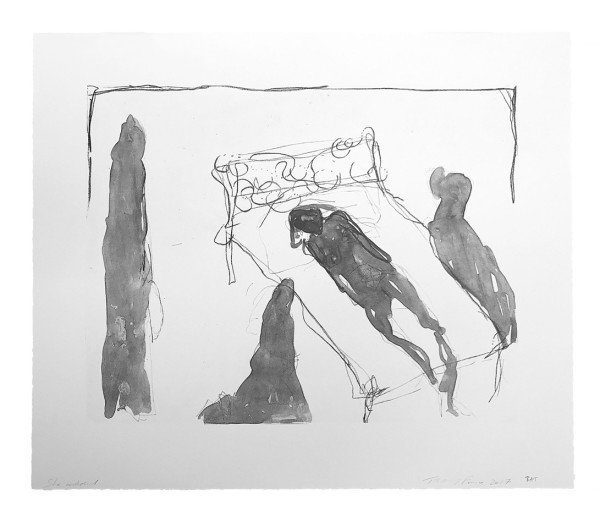

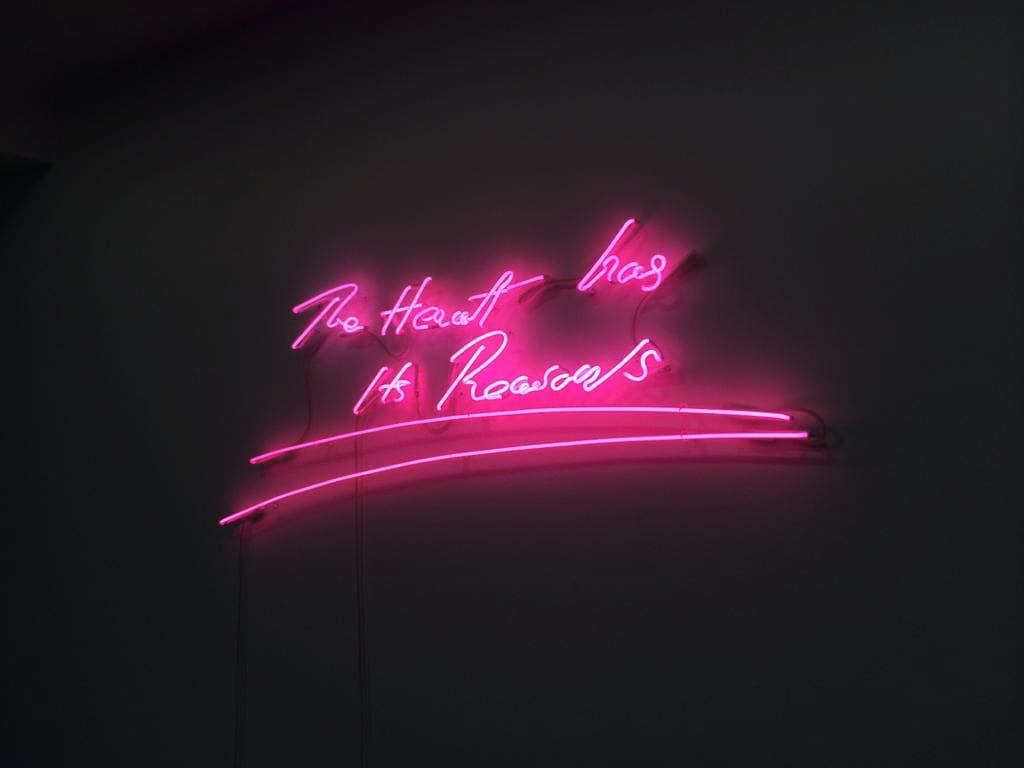

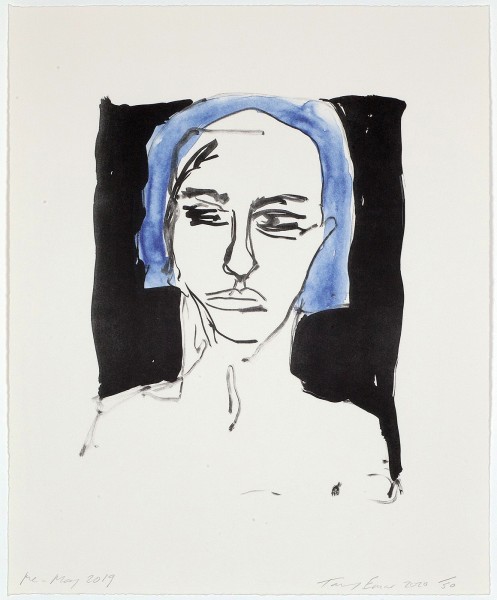

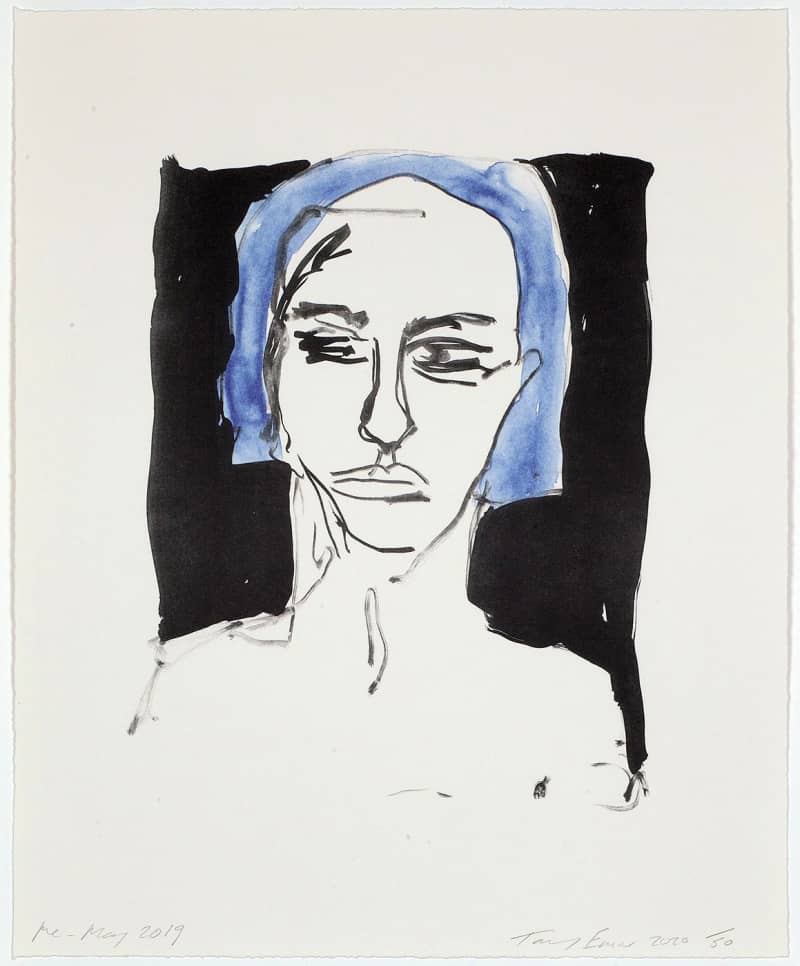

Tracey Emin is a highly decorated multi-media artist who lives and works in London. Working alongside the likes of Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn and Sarah Lucas, Emin has celebrated an eminent career over the past two decades, being nominated for the Turner Prize as well as becoming a Royal Academician. Just last year in 2020, Emin’s work exhibited at the Royal Academy alongside Edvard Munch in a show entitled, The Loneliness of the Soul. Offering a frank examination of her own life, sex and the human body, Emin’s work has both won her critical acclaim and expanded the limits of contemporary art for future female artists.

By the time Emin rose to prominence in the late 1990s, many British female contemporary artists had begun to pave the way for her success. In 1993, Rachel Whiteread became the first ever female artist to win the Turner Prize; an award that in 1997, had its first ever all female shortlist, including Christine Borland, Angela Bulloch, Cornelia Parker and the winner, Gillian Wearing. Emin had emerged during a time where contemporary female artists were finally receiving recognition; this provided her with a new and unique stage upon which to challenge the current perceptions and boundaries of the world of contemporary art.

In 1999, Tracey Emin aired her dirty laundry in her germinal work at the Tate Modern, entitled My Bed (1998). Catapulting her to fame, the installation featured Emin’s own bed scattered with the detritus of a bad break-up, and including everything from empty vodka bottles, to condoms and cigarettes. Emin had reportedly remained in her bed for four days before proceeding to exhibit the contents. A stark examination of Emin’s most vulnerable moments, My Bed unapologetically ignored social conventions. This is typical for Emin’s work and consequently, much of her oeuvre is incredibly intimate, featuring nudity, sex and a personal insight into much of her own life.

Despite other female artists having interrogated these themes prior to Emin’s emergence - including performance artists Marina Abramovich and Carolee Schneeman - Emin’s work was the first to be accepted by mainstream culture and exhibited in both the Royal Academy and the Tate. Prior to this, many of the topics Emin was actively confronting were considered avant-garde and would have been excluded from the exhibitions of leading institutions.

Whilst Emin’s acceptance into mainstream culture may have been unprecedented, by this point Japanese visual artist, Yayoi Kusama, had been a favourite in the world of contemporary art for decades.

Unlike her contemporaries, however, Kusama’s rise to recognition was considerably slower, and stunted by both her gender and race. As a young female Japanese artist in New York in the late 1950’s – a time still plagued by the attack on Pearl Harbour and the subsequent xenophobia – the city was not a welcoming place. Following in the footsteps of Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, Kusama also had to work twice as hard to gain recognition, combining her talent with both diligence and persistence to drive her career as an artist.

In an attempt to broaden her reach, Kusama channelled her creativity into startingher own fashion line, Kusama Enterprises, in the late 1960’s. Her dresses, decorated in her signature spots, were a hit and garnered her great attention. As a result of her gender, it was necessary for Kusama to strategically self-brand and by expanding into fashion, Kusama was able to masterfully manoeuvre herself into the public eye.

During her time in New York,Kusama befriended influential American artists such as Donald Judd, Georgia O’Keefe and Eva Hesse. Although Kusama’s work was influenced by Abstract Expressionism and pop art, her style was and remains completely unique. In recent years, Kusama’s rare and distinctive works have had a resurgence in popularity and caused a unique stiracross social media. Featuring shining lights, interactive installations and mirrors primed for selfies, Kusama’s reach – with the help of Instagram – now spans further than ever before.

From happenings and installations to prints and sculptures, Kusama’s career has been long and illustrious. Whilst her choice of medium has changed throughout time, the core essence of her work has remained. Focussing on repetition, obsession and visualising her own hallucinations, Kusama’s command of colour and shape is second to none. Her raw talent, hard-work and perseverance has meant that over her fifty-year career, she has been able to build an incomparable reputation. With her Infinity Rooms set to exhibit at Tate Modern next year, Kusama’s enduring success seems increase year on year.

YAYOI KUSAMA, PUMPKIN (A), 1990