From Andy Warhol’s renowned Campbell’s Soup cans to Banksy’s infamous critique of consumer culture, we discuss how artists from around the world broke down the barrier between everyday objects and fine art

From the pop art of the 1960s to contemporary brand collaborations, global art will always be inextricably linked to wider consumer culture – after all, art, like other passion investments is an object that, more often than not, can be bought for the right price. However, the relationship between fine art and everyday brands is not as straightforward as it is with luxury goods. From embracing the cult of consumerism to critiquing it, we map out how budget brands became the subject of fine art.

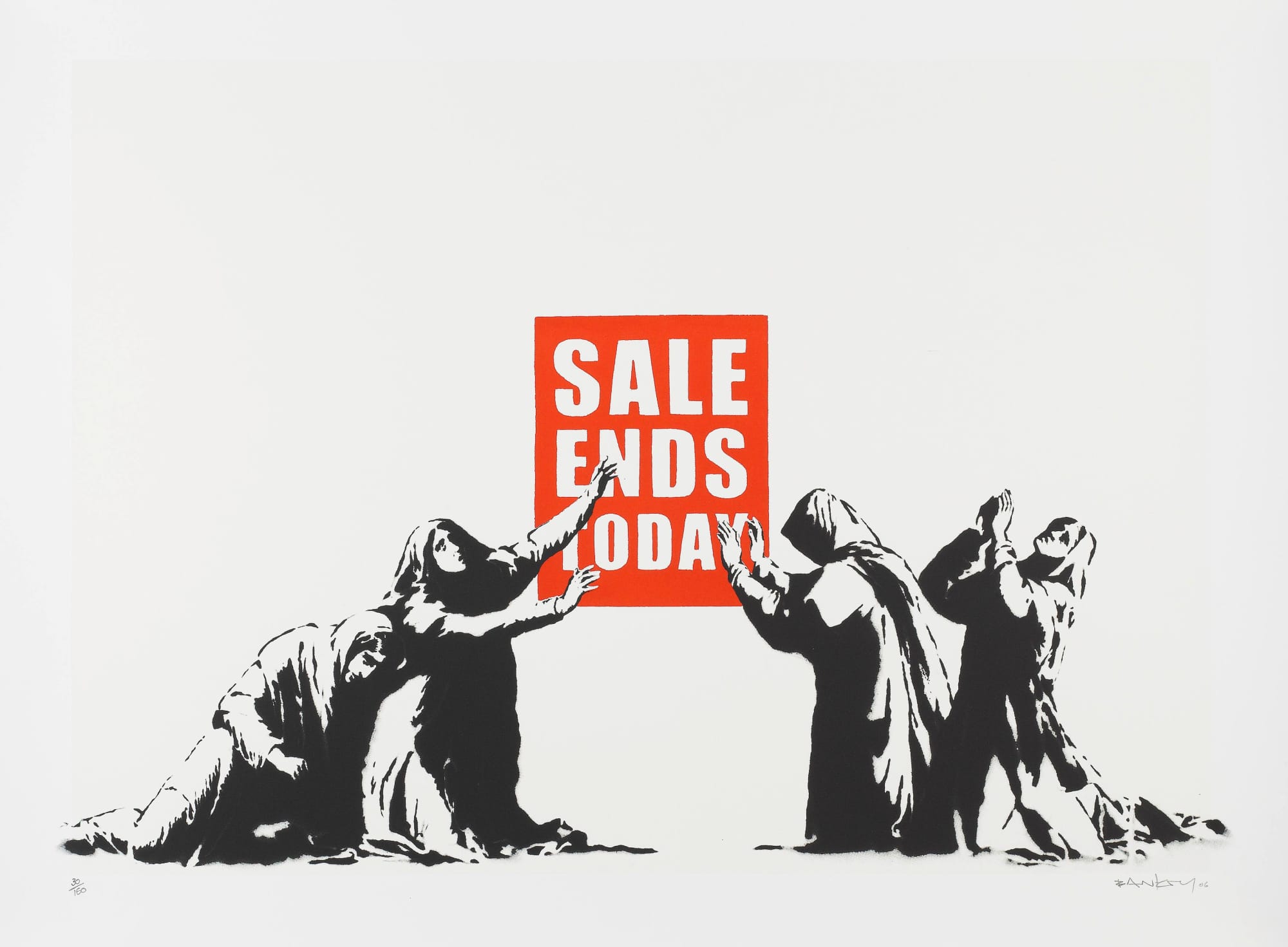

BANKSY, SALE ENDS V2 (SIGNED), 2017

The Pop Revolution

In the 1960s, the pop art movement and more specifically Andy Warhol began featuring every-day objects in art. Just a decade earlier, the elitist nature of Abstract Expressionism had rendered art impenetrable to the masses and pop artists were on a mission to make sure that art could be enjoyed by the many, not the few. Taking well-known products from ubiquitous brands like Campbell’s Soup, Brillo and Coca-Cola, Warhol transformed commonplace objects into revered works of fine art, offering the public an opportunity to climb the art market’s ivory tower, peering in and gaining access.

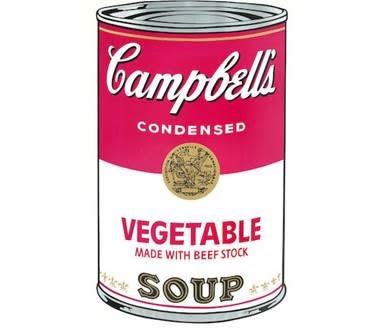

One of Warhol’s most famous renderings of an everyday item is his Campbell’s Soup series. Using a range of methods from stamping to painting, Warhol’s series depicts over 32 different flavours of the iconic soup. On the work Warhol reportedly noted that he “used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years . . . the same thing over and over again”, and the artist’s screen-printing process mirrors this, highlighting the banality of this bargain brand. By including such a universally recognisable product in his work, Warhol was inviting a wide audience to appreciate his artwork, with a subject matter that was accessible to everyone.

ANDY WARHOL, VEGETABLE SOUP, 1968

Critiquing Consumerism

In stark contrast to pop art’s embrace of the big brands, anonymous street artist Banksy is known for his disdain for consumer culture, mocking corporations with his satirical murals and prints. Taking French personal care company L’Oréal’s recognisable slogan, ‘because you’re worth it’ and changing it to a more pessimistic motto, in Because I’m Worthless Banksy pokes fun at both the exploitative techniques that big brands employ to ensnare customers as well as the customers themselves for partaking.

BANKSY, BECAUSE I’M WORTHLESS, 2004

Ironically, in recent years Banksy’s success has led him to become part of the very culture he is aiming to critique. In 2018, Girl with Balloon (2006) by the Bristolian street artist went for auction at Sotheby’s. On the final strike of the hammer settling the purchase, the artwork began to auto-destruct, shocking audiences tuning in around the globe. The partially shredded work was renamed Love Is In The Bin and the work both immediately and dramatically increased in value. Many argue that Banksy’s stunt was an act of rebellion against consumer culture, critiquing a society where material objects reign supreme. However, his act of destruction only drove prices higher, paradoxically fuelling the consumer market.

BANKSY, TROLLEY HUNTERS B&W, 2006

Shopping Makes The World Go Round

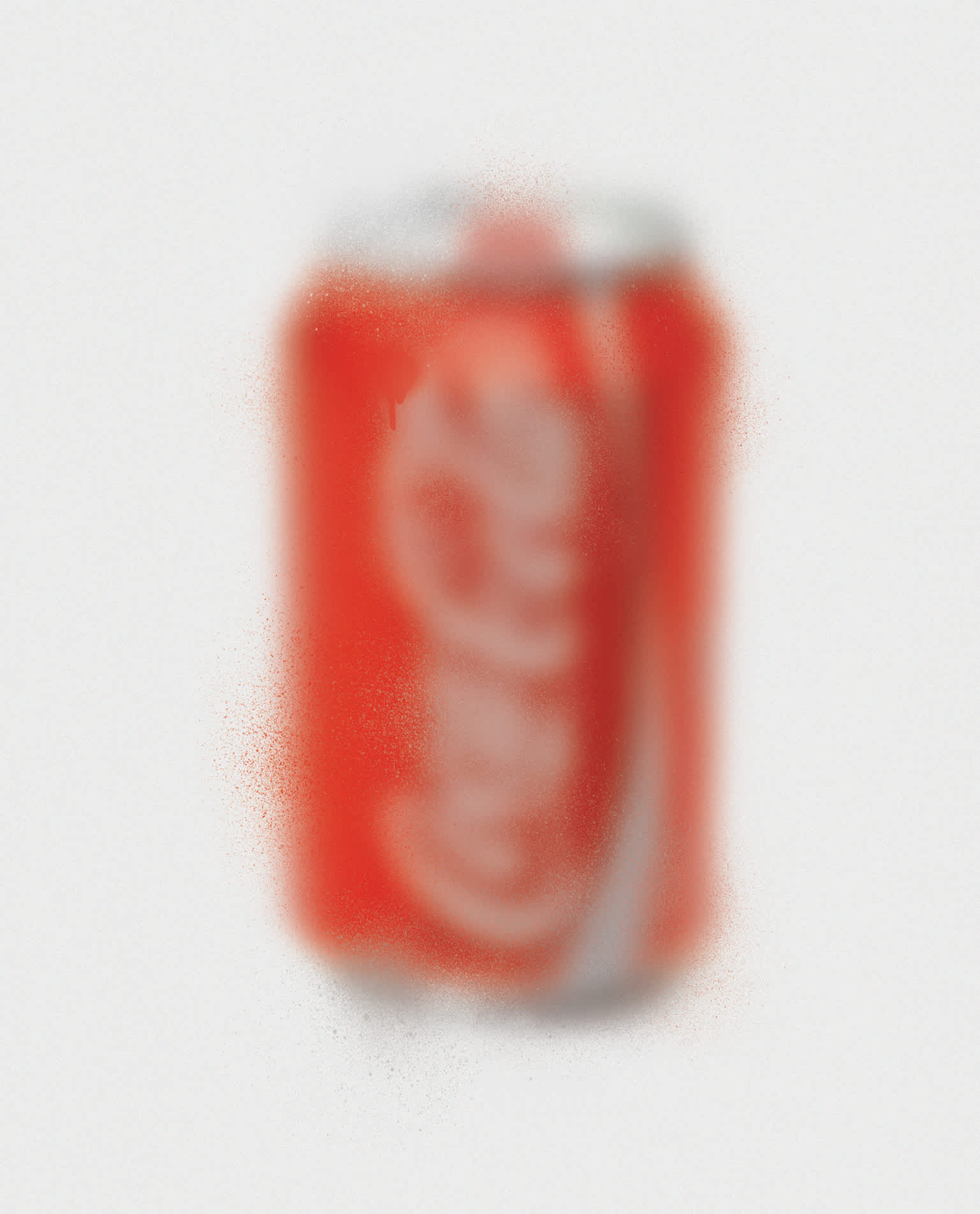

It is undeniable that brands are everywhere. From iconic packaging to catchy slogans, global marketing dominates our subconscious and permeates every facet of popular culture. Therefore, when an artist wants to reinterpret a well-known image or inspire a sense of familiarity, what better place to turn than cut-cost products, universally appreciated by all. The internationally dominating Coca-Cola brand has often been a favourite choice of artists when embarking on such endeavours due to its vibrant red packaging and sleek white typography. The brand has famously been incorporated in artworks around the globe by the likes of Andy Warhol, Marisol and Cildo Meireles, to name just a few.

In 2020, the Miaz Brothers, known for their nebulous renderings of objects, also turned to the fizzy drink for inspiration. Creating canvases and prints that appear at once both familiar and estranged, the artistic duo play upon the viewer’s own imagination and memories to fill in the gaps and evoke emotion. As the Coca-Cola branding is so iconic, their out-of-focus depiction is easily identifiable, thanks to the omni-present nature of the company.

MIAZ BROTHERS, COCA COLA CAN, 2020

What If Nike Is The New Medici?

Over the past two decades, popular consumer brands have begun to embrace the symbiotic relationship between art and commerce with companies like Uniqlo, PepsiCo and Nike collaborating with and patronising both aspiring and established artists.

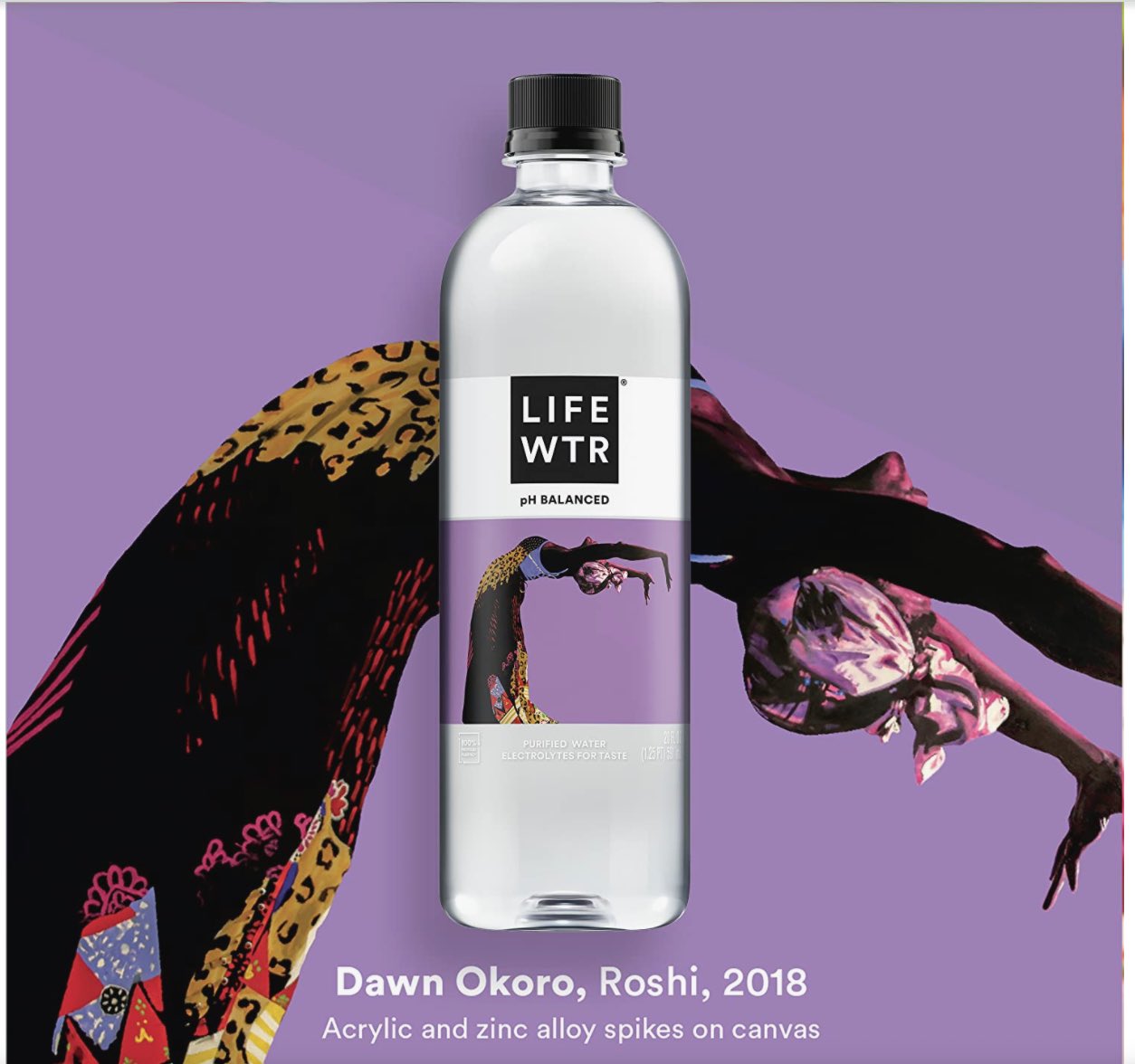

For example, in 2020, Maddox signed artist Dawn Okoro captured the attention of multinational company PepsiCo. Featured as part of their Black Art Rising series with their daughter company LIFEWTR, Okoro’s artwork was featured on their bottle, as well as the artist talking about her creative journey on the CEO of PepsiCo’s podcast, In Your Shoes.

DAWN OKORO’S COLLABORATION WITH LIFEWTER FEATURING ROSHI (2018)

Although luxury brands, like BMW and their renowned Art Cars, have interacted with artists since the 1970s, from the turn of the millennium, there has been in increase in every-day consumer brands working with creatives, prompting the question and art-world in-joke ‘what if Nike is the new Medici?’ Acknowledging the shift of patronage from wealthy individuals, like the 15th century Florentine family the Medici’s, to global corporations like Facebook, Google and Adobe, the phrase is less absurd than it seems. In less than 80 years, art has gone from glorifying banal consumerism, to critiquing it, to embracing and even becoming synonymous to it. Whether its soft drinks or software, day-to-day brands we all use are collaborating with artists, further blurring the already hazy lines between fine art and consumer companies.