With a scarcity of blue chip art available and increasing demand for investment-grade works, a phenomenon called “red chip art” has developed. We examine this concept of red chip art, and what investors need to know about collecting during the rise of red chip art.

People say that three things in life are certain: death, taxes, and Picasso holding reign as the world’s most sought-after artist. However, following two years of a pandemic, things that once seemed inevitable are no longer certain. Despite the art market’s resilience throughout 2020 and 2021, the industry has still been shaped by the global events following COVID-19. With a scarcity of blue-chip artworks available and demand for investment grade works at an all-time high, a new phenomenon called red-chip art developed, changing the art market forever. We examine this new investment grade and tell you everything you need to know about collecting during the rise of ‘red-chip’ art.

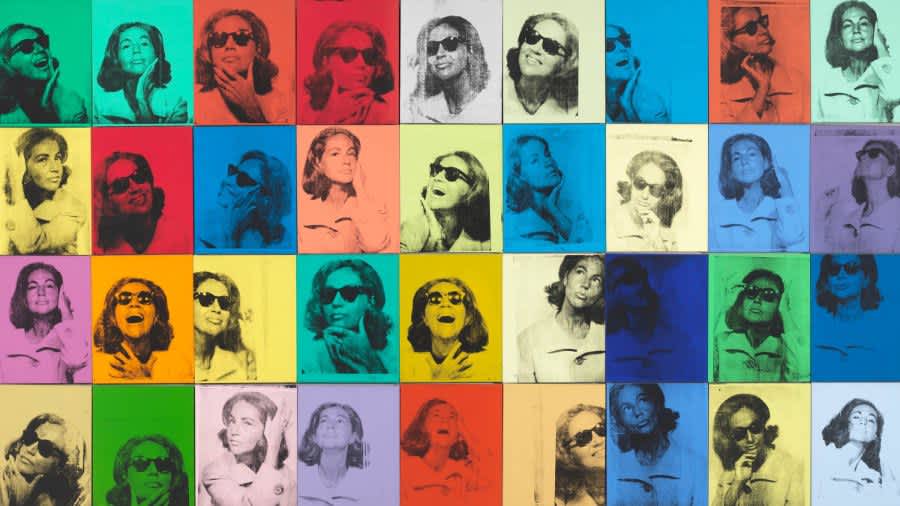

KAWS, YOU SHOULD KNOW I KNOW, 2015

What is blue-chip art?

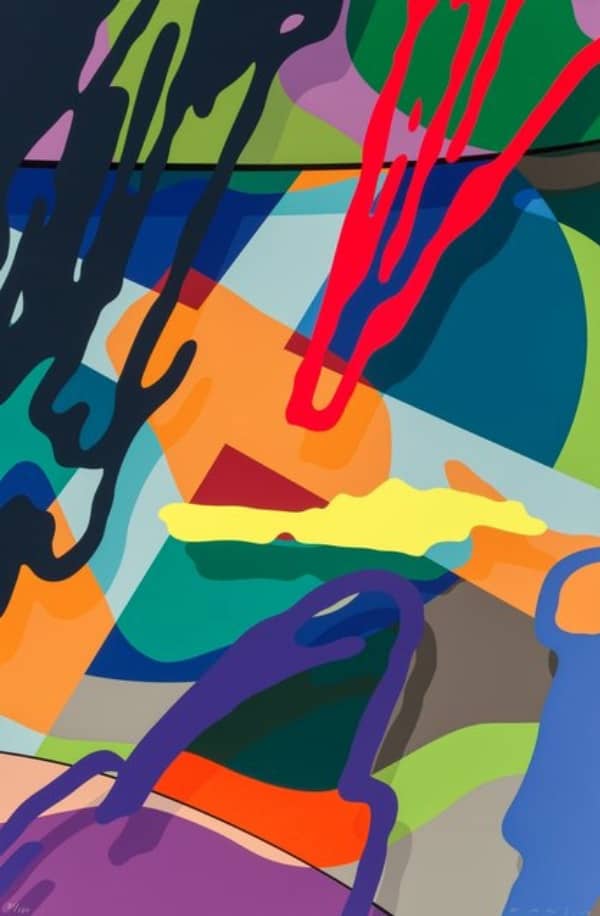

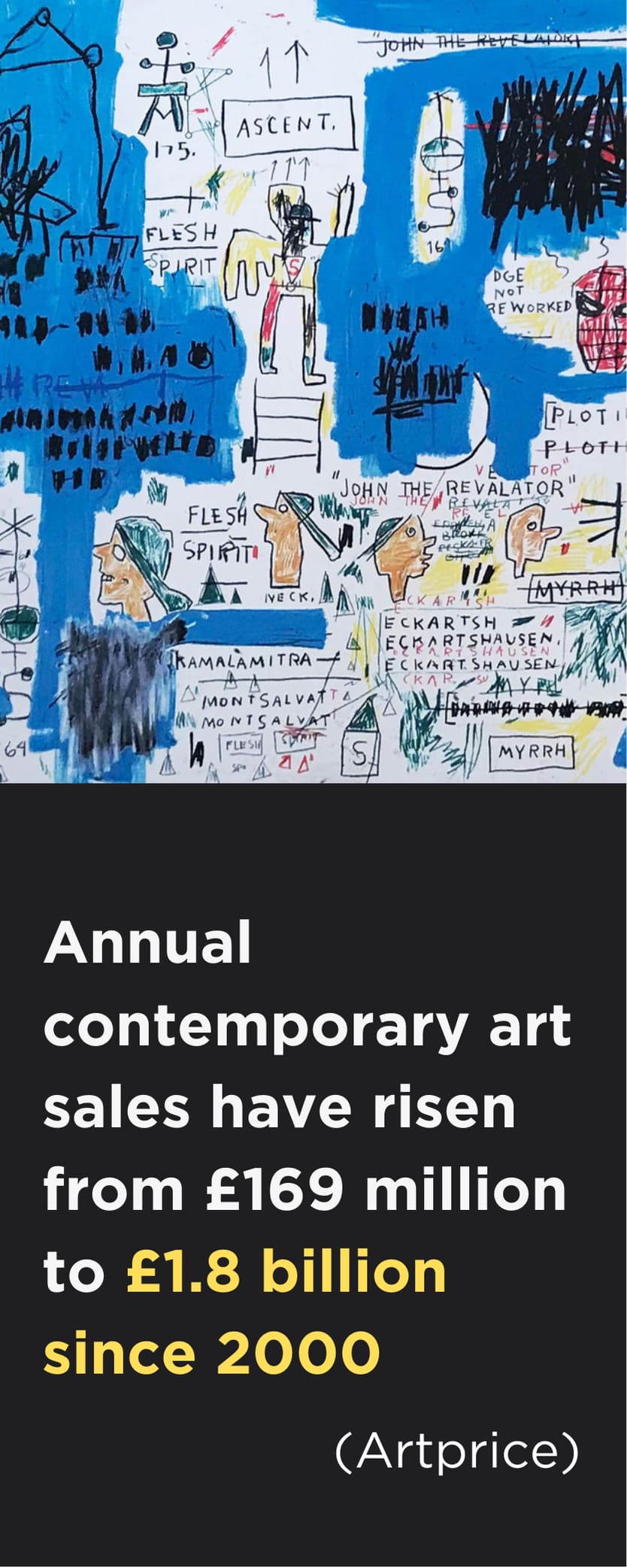

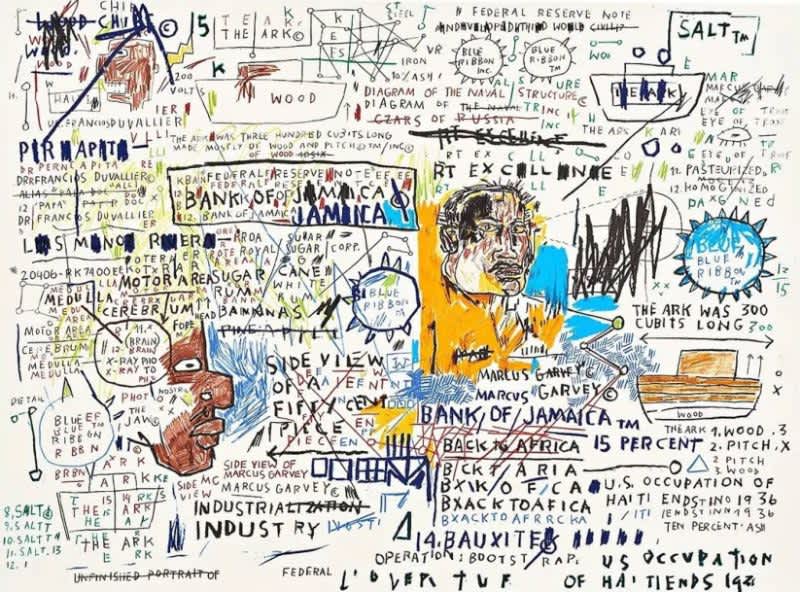

To understand blue-chip vs. red-chip art, we must first quickly recap what is meant by blue-chip art. Blue-chip artwork is, unsurprisingly, created by blue-chip artists. These artists, like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol, are well-established and globally recognised. Their academic legitimacy has cemented them as key players in art history, affording them consistent auction results and a resilient marketplace where the value of their work will either hold or increase despite general economic fluctuations. Their artworks tend to fetch record-setting auction results and consequently, these “trophy” pieces are in high demand but in low supply – a perfect recipe for a bidding war amongst high-net-worth art collectors.

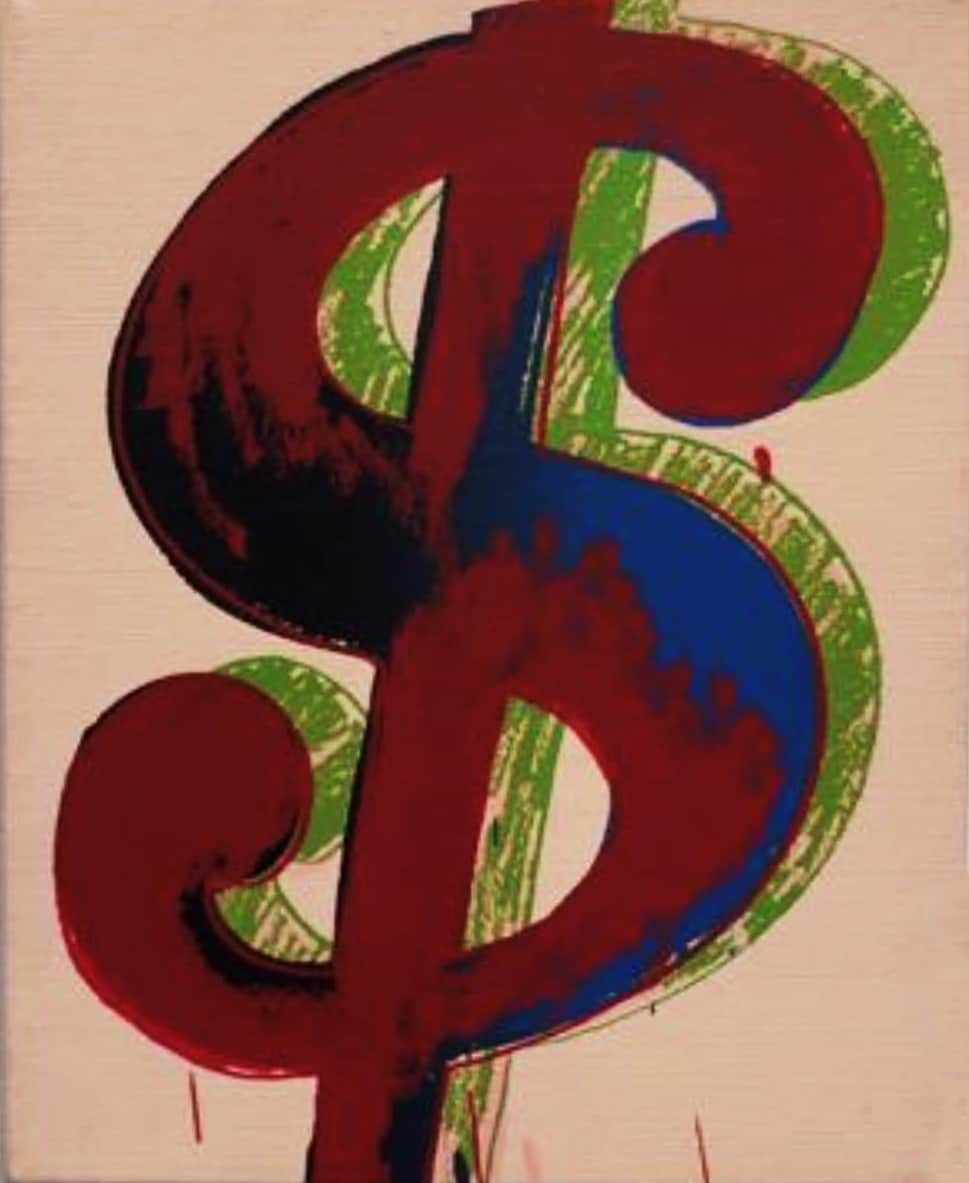

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, 50 CENT PIECE, 1983/2020

Blue-chip art and the pandemic

Art is a great tangible investment asset as it has the capacity to preserve value and act as a hedge against inflation. Therefore, during times of financial distress, owners of blue-chip artworks usually withhold their most valuable masterpieces to protect their capital. As a result, this causes a scarcity of blue chip art investment opportunities while demand is at its peak – and this is exactly what we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many investors looked to diversify their portfolios by acquiring art, but few collectors were willing to sell their blue-chip work in a time of economic depression. As a result, a new investment grade of art emerged to fulfil the unprecedented demand: red-chip.

ANDY WARHOL, DOLLAR SIGN, 1982

What is red-chip art?

Red-chip artists are often younger, emerging artists who are both creating new works on the primary market, while at the same time, selling their works for dizzying prices on the secondary market. Skipping the traditional artistic progression of relying upon galleries or dealers to advance in their career, these emerging new talents utilise social media to self-promote their work, achieving extraordinary commercial success in a very short time span.

What does the rise of red-chip mean for artists?

With over one billion monthly active users on Instagram, the use of social media has brought a revolution to the art ecosystem for both artists and collectors. For artists, the rise of red-chip promises a more democratic art market, as creatives can pave their own path to success without having to submit to the tastes and expectations of elite art institutions. In addition to this, the rise of social media can facilitate meaningful connections between artists, buyers and key market players, creating important networks and offering the opportunity for artists to have instant public feedback in the form of ‘likes’ and ‘comments’. Furthermore, Instagram allows new collectors from emerging economies to join the art market, diversifying taste and artistic trends.

What does this mean for collectors?

The rise of red-chip art is just as advantageous for collectors as it is for artists. Not only has red-chip art filled collectors’ insatiable appetite for blue-chip work, but the digitalisation and globalisation of the art market has also expanded the pool of creative talent. In addition to this, red-chip art provides low-price entry artworks that may grow into attractive investment returns should the emerging artist rapidly rise to fame.

The New Mega-Dealer – Instagram & the legitimisation of street art

With all of this in mind, it is easy to see why Instagram has been dubbed the ‘world’s new big art dealer’. In a market where dealers and institutions once held the authority, power dynamics are shifting. Due to crowd-sourced governance, influence is dictated by the masses rather than traditional figures and critics, which has already led to changing tastes within the market.

An excellent example is Instagram’s role in the legitimisation of street art. With 11.2 million followers on Instagram, anonymous artist Banksy has a far larger audience than Christie’s (980K), Sotheby’s (1.4M) or any mega-gallery could dream (Gagosian has 1.8M). His influence, especially during the pandemic, has been as wide-reaching as it has been significant. Banksy’s online presence, as well as Instagram’s ability to act as a medium to preserve a visual memory for street art has all fed into the genre’s legitimisation. In 2019, the term #streetart was featured 26 million times on Instagram and just two years later, in 2021, the hashtag was used over twice as many times with the tag appearing 60.5 million times throughout the year. This metric alone exemplifies the influence Instagram has already had on the art world over the past three years and acts as a harbinger for the increasing involvement social media will have in the art market.

The value of investments can go down as well as up, and past performance is not guarantee of future performance. Return figures shown are gross; fees, including a 20% performance commission, may apply. Liquidity is not guaranteed. Terms, limitations, and withdrawal conditions apply. Minimum recommended investment is £20,000. Maddox Advisory is not FCA-regulated and does not give financial advice. Seek independent advice before investing.