From the subway system to World Fair pavilions, we look at the artists who have created art outside of a studio setting.

As coined by the great Keith Haring, the statement that ‘art is for everybody’ has never been more widely endorsed than today, with cities and regions all over the world celebrating public art more than ever before.

One such city is Montreal, which launched its seventh edition of Festival Mural last week. This eleven-day event champions art outside of the studio setting and has seen artists cover everything from basketball courts to the façades of high-rise buildings with their unique designs. This event comes as one of many celebrating public art, with London also hosting its first ever mural festival in 2020. No matter where you are in the world, whether on the side of a derelict building or on a subway car, art is all around us, if only you just look up.

From street artist’s using their city as a canvas to contemporary artists thinking (and painting!) outside the box, we look at five artists who are taking art beyond the gallery walls and explore how taking their work out of a formalised context can enhance or change the artwork’s meaning.

Keith Haring

Famous for his street art, in 1980 Keith Haring made his name creating artwork in advertising panels in subway stations. Noticing that unused public advertising panels were covered in matte black paper, Haring began to create chalk drawings throughout the subway system. Between 1980 and 1985, the artist produced hundreds of these drawings, sometimes creating as many as forty in one day. However, due to the ephemeral nature of advertisement, few remain.

Haring famously stated that ‘art is for everybody’ and by using the subway as his canvas, he ensured exactly this. His artwork was accessible to everyone. Creating art outside of a gallery setting ensured a bigger audience for his work and meant that his distinctive vernacular was recognised by everyone from children to the elderly.

KEITH HARING, SUBWAY DRAWING, 1981

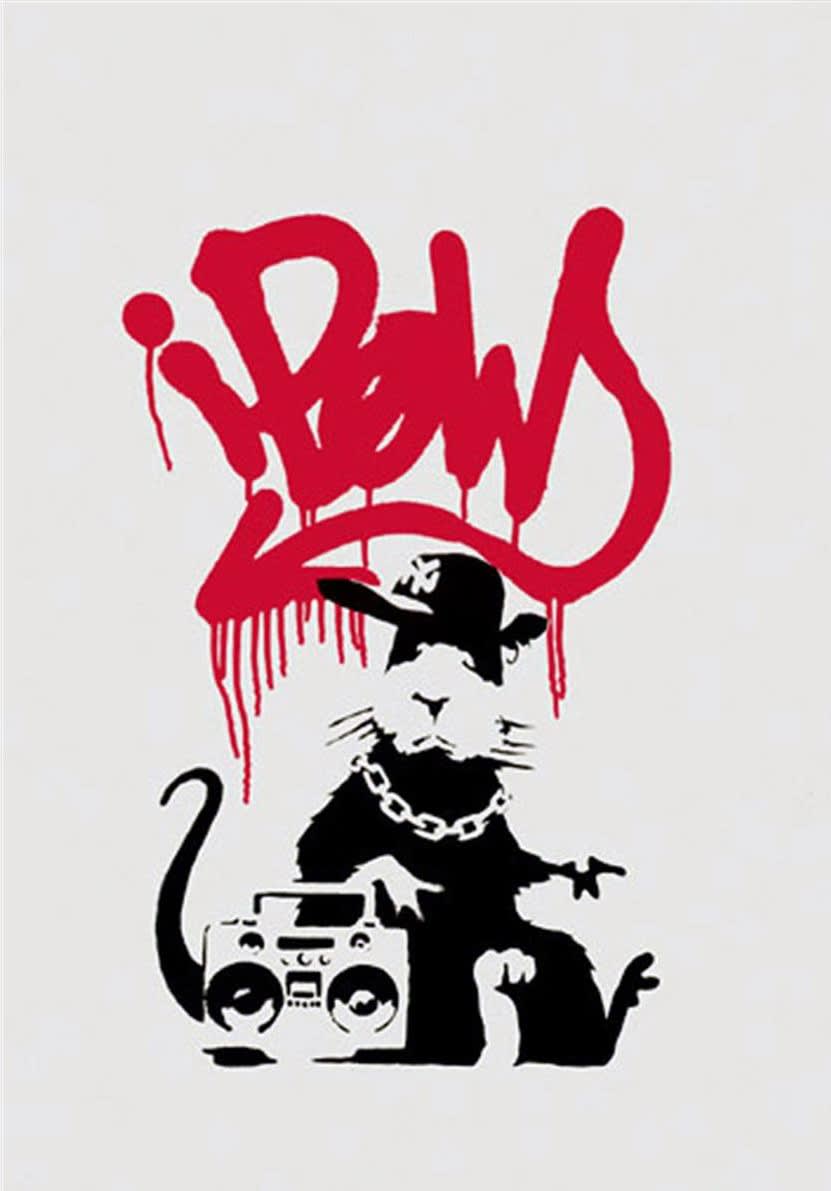

Banksy

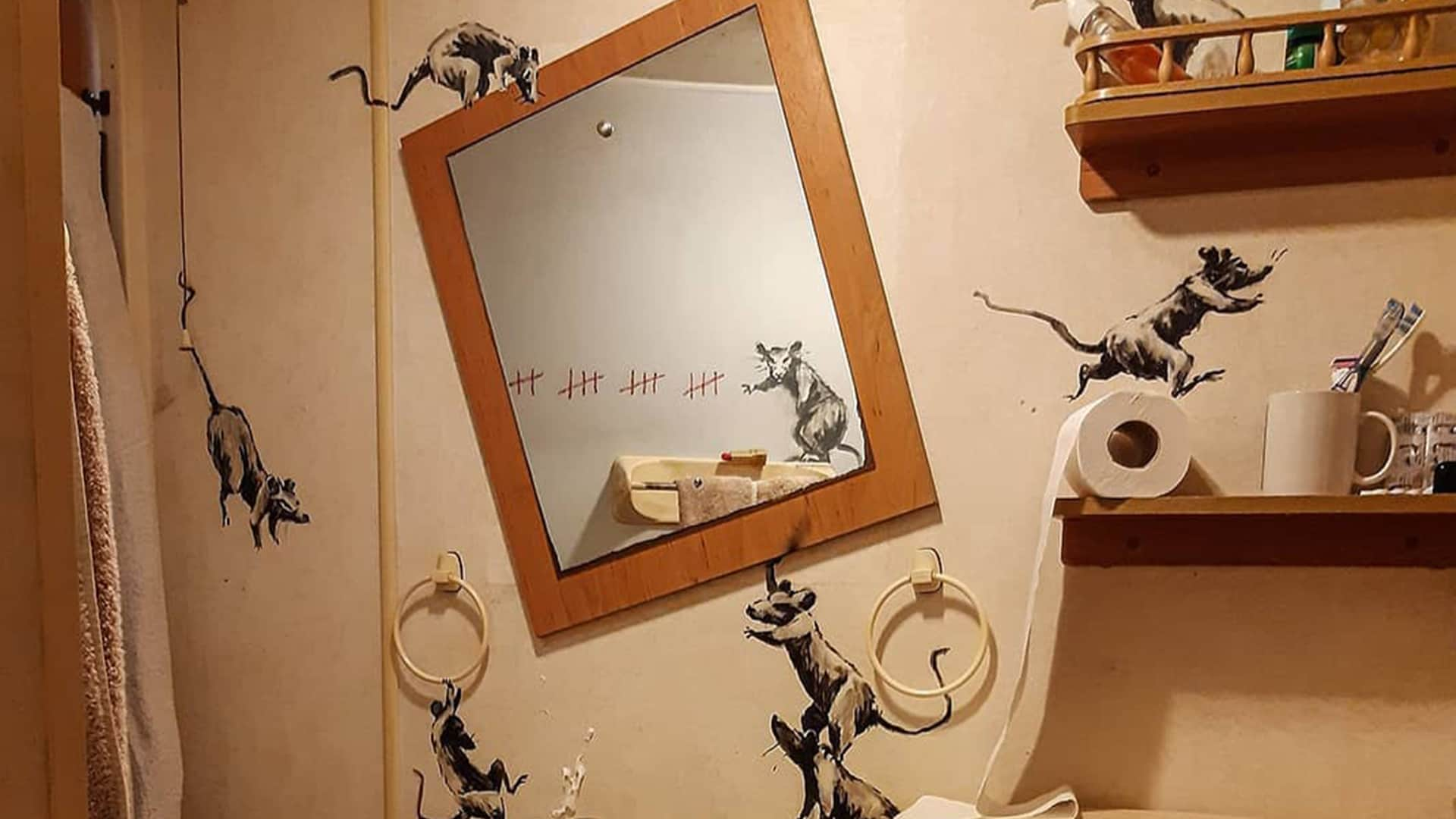

Known for his graffiti murals, Banksy is one of the most prolific street artists in the world. Famously critical of art institutions, Banksy often turns to unexpected locations to create his murals and even during a global pandemic, he couldn’t be stopped.

In April 2020, as the United Kingdom was in a national lockdown, the street artist shared his latest work to his 10 million followers on Instagram with the caption ‘my wife hates it when I work from home’. The photograph saw a domestic bathroom overrun with the artist’s signature rats, causing chaos by swinging on mirrors and unravelling toilet paper. The humorous image received over 2.5 million likes on social media and brought joy to the world when we needed it most. Banksy’s post proved that even when galleries and museum were shut, art can live on beyond the walls of institutions.

Lefty Out There

Lefty Out There creates bold and intricate artworks made up of cell like structures, that are at once organic and uniform. His signature squiggles have adorned surfaces across Europe, the United States and Asia, covering walls, apparel and even skin.The very nature of his sprawling designs defy containment. For Lefty Out There, his goal is to cover the world with his art, meaning that everything is a canvas. His work engulfs spaces, his familiar pattern coming alive on surfaces. His art cannot be confined. To contain his artwork to a gallery space alone would undermine both Lefty’s manifesto to ‘cover everything’ and limit the vitality of his dynamic designs.

Next month, Lefty will be undertaking his tallest mural yet, painting a 70ft black and white design on the side of a property in Chicago. The project is in collaboration with @properties, Chicago’s top real estate company.

LEFTY OUT THERE, UMBRA MAGNA, 2019

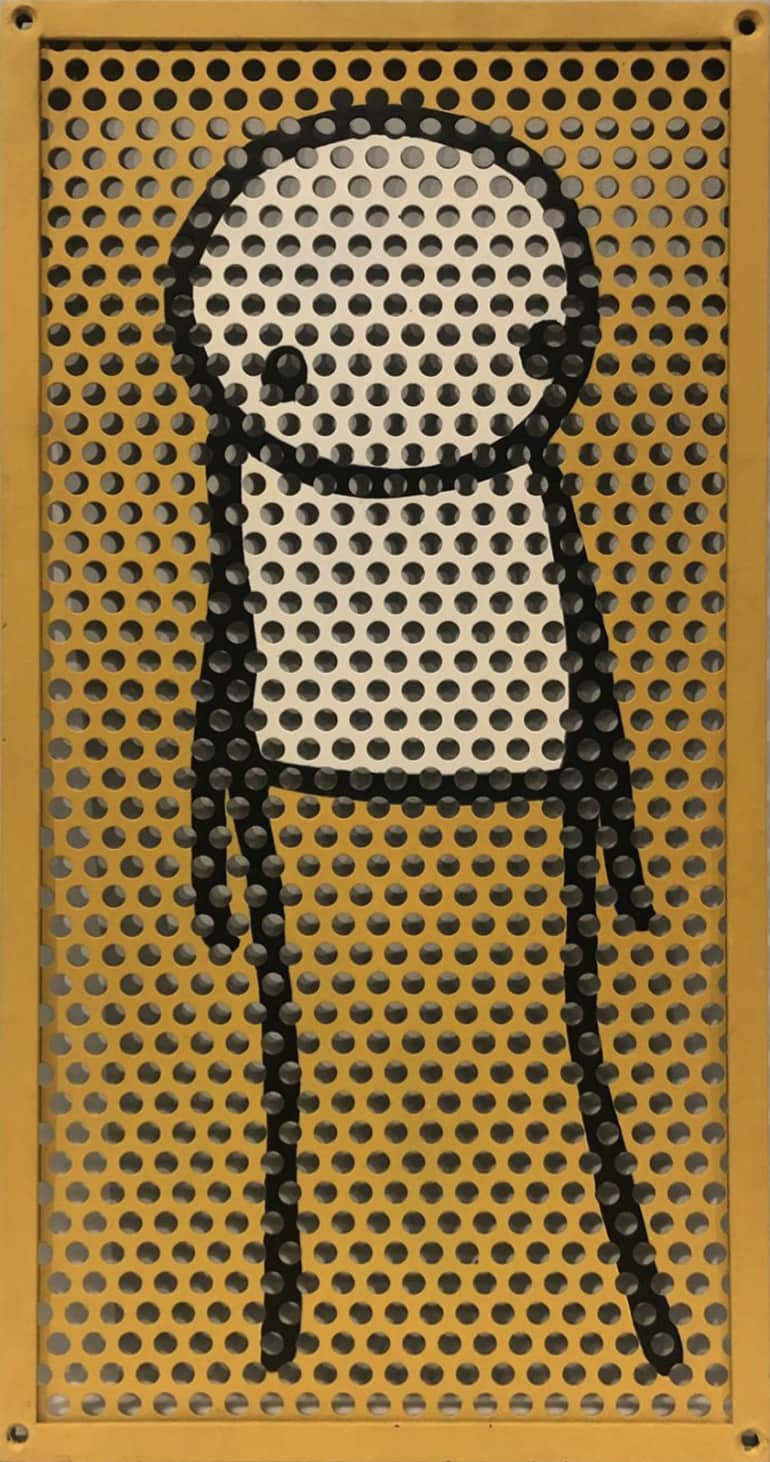

STIK

Anonymous street artist STIK is no stranger to using anything and everything as his canvas. From oil recycling plants in Japan to wind turbines in Norway, STIK creates site-specific murals that reflect their surroundings. The meaning of his work is often amplified by its location, meaning that to relocate his murals within a gallery or museum would disarm the power of his art.

For example, in 2016, STIK painted Past, Present & Future on the corner of Old Street in Shoreditch, London. The artwork sees three of STIK’s signature figures standing in a row. The artwork looks over the former artist district of Shoreditch and according to the artist ‘the first figure looks longingly back on Old Street where artists once thrived, the second peers out at the encroaching billboards, uncertain of how long the few remaining artists can afford to stay, [and] the third teeters precariously, to succeed or move on is yet to be seen’. The specific location of the artwork creates context and meaning that would be obsolete in any other location, let alone, inside an art institution.

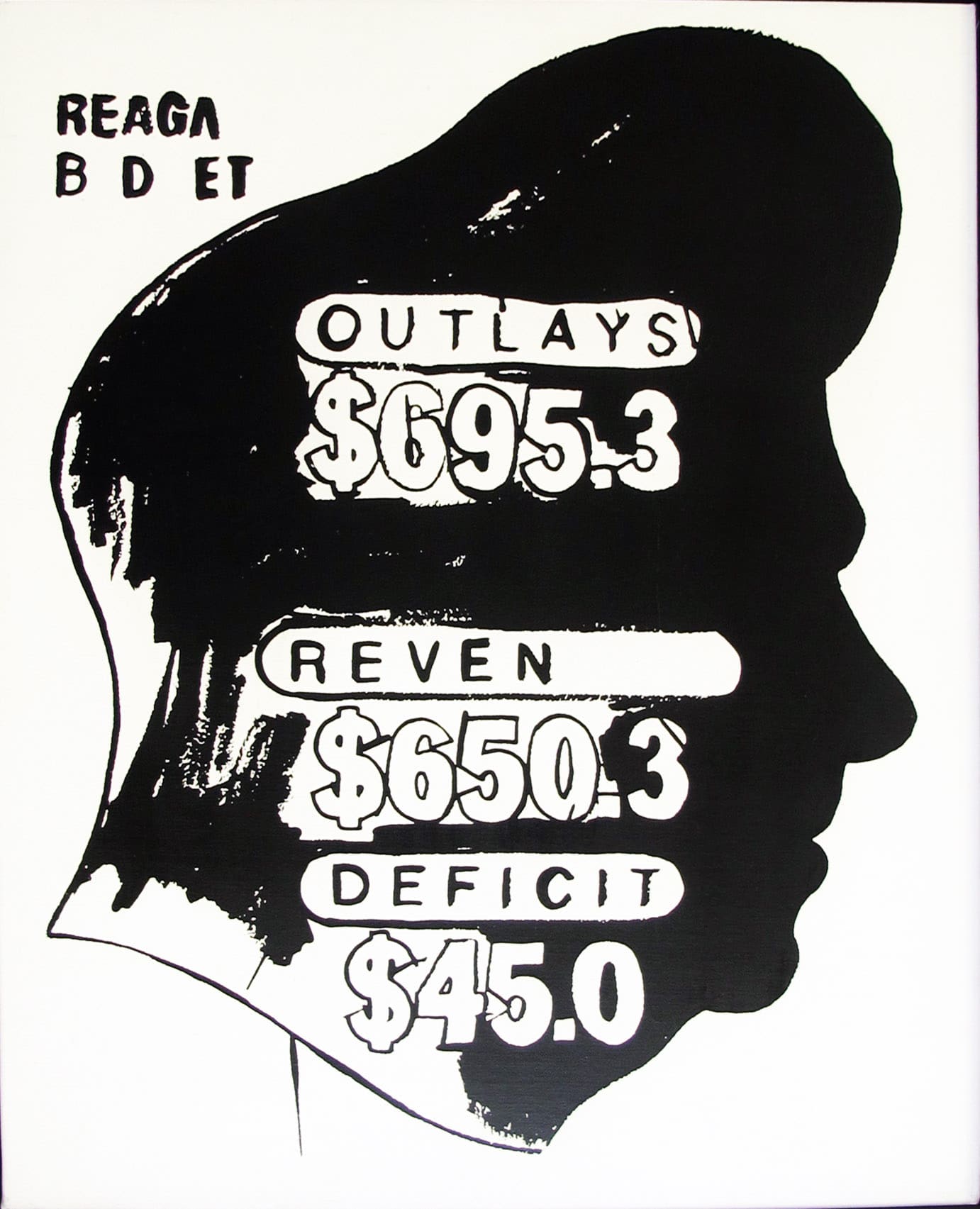

Andy Warhol

Throughout his career, Andy Warhol pushed the boundaries of art in many ways, from his everyday subject matters to his innovative printing methods that defined the pop genre. However, with innovation often comes provocation.

In 1963, Andy Warhol was commissioned, alongside nine other artists to create a monumental artwork that was ‘to do with New York’ to adorn the exterior of the Panoramic Cinema Theatre in Flushing Meadows, New York. The curved concrete building would serve as the epicentre of the 1964 World’s Fair and Warhol’s artwork would be front and centre. Warhol’s artwork was entitled Thirteen Most Wanted Men and it depicted twenty-two mugshots of wanted criminals, spanning over 20 feet. The artwork only remained on the outside of the construction for a few days before it was covered up, with the fair’s organisers covering the work in aluminium paint.

There are many speculations as to why the work was censored. Some argue that Warhol was unhappy with the work, other’s say that it would have caused offence to important Italian political lobbyists as a large number of the subjects were of Italian-American descent. More recent theories as to the work’s censorship also include the homo-erotic undertones of the artwork. However, whatever the reason, it is undeniable that the work’s public location, outside of a gallery context, politicised the artwork and led to its destruction, proving that when artist’s take their work beyond the gallery walls the meaning is enhanced and often transformed.

ANDY WARHOL, REAGAN BUDGET DEFICIT (POSITIVE), 1985-86